David Peck is an associate professor in the faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment at TU Delft. He is specialized in critical materials and circular product design.

- Many criteria for a circular economy were met during World War II.

- Some government policies are needed to increase the speed of the energy transition.

As consumers, we mainly notice the shortages in sunflower seeds, grain, caused by the war in Ukraine, and the shortages in computer chips that is a result of the COVID pandemic. But there are more shortages, especially impacting the resources needed to accomplish the energy transition. In his PhD-thesis, Peck analysed various response strategies to resource constraints. “We can learn a lot from how governments have tried to resolve these issues in the past.”

Shortages of all ages

Europe wants to reduce its raw material use and carbon emissions by 50 percent in seven years from now. Back then, the United Kingdom achieved this in only two years, so there are lessons to be learned.”

During World War II, world markets and the supply chains of many materials were adversely impacted on an unprecedented scale and many countries struggled with rampant shortages. Between 1940 and 1944, targeting of transport vessels resulted in commodity shipments to the United Kingdom dropping by 50% while demand remained high. “The technology and the geopolitical situation were completely different back then, as were the kind of materials that were in short supply,” Peck says. “You could argue that this makes an invalid comparison. But we must realise that specific materials can literally define an era, think of the Stone Age and the Bronze Age. Nowadays, it is lithium and cobalt.”

The past can also serve as an example when considering the urgency of the present challenges. Peck: “Europe wants to reduce its raw material use and carbon emissions by 50 percent in seven years from now. Back then, the United Kingdom achieved this in only two years, so there are lessons to be learned.”

License to operate

During his PhD, Peck did not look at the production of weapons. He rather studied ordinary products such as clothing, pottery, and furniture. “During war, laborers still need a bed to sleep, a table to eat at, and a plate to eat from. Therefore, these were essential products to be produced during war time.” One of his primary interests involved the policies set by the British government through which they intervened in any and all production. “A license to operate became obligatory and private companies worked under government contracts. The government decided what would be designed and produced, to make sure the economy would continue to function.”

The British government took complete control, altogether changing the structure of supply and demand. They appointed six senior policymakers, with another six industrialists being responsible for certain industrial sectors. Peck: “These twelve men basically sat down and said: this is what we have, this is what we want to make, and these are steps we need to take to make it work. Production of non-essential products was put to a halt.”

Unintentionally circular

In a normal market, production would cater to what is likely to sell. In Britain during World War II, however, it was up to a panel of designers to come up with the most efficient products designs, such as minimalistic furniture. “It had to be cheap, require little and preferably locally sourced material, and had to be easy to manufacture,” Peck says. “Nobody knew when the war would end, so they were built to last. Some chairs are still collectors” items as they were so well made.” The government also issued ‘make do and mend’ pamphlets, providing housewives with useful tips on how to be both frugal and stylish in times of harsh rationing. “Unintentionally, they were quite environmentally conscious. I find it very interesting that many of the criteria for a circular economy were met during the war.”

Yet another shortage

We are moving in the right direction, but not fast enough. The supply chains of critical materials are extremely dynamic and complicated. There are thousands of questions that need answering but, with all scholars specialised in this topic fitting into a single meeting room, we lack sufficient research capacity.”

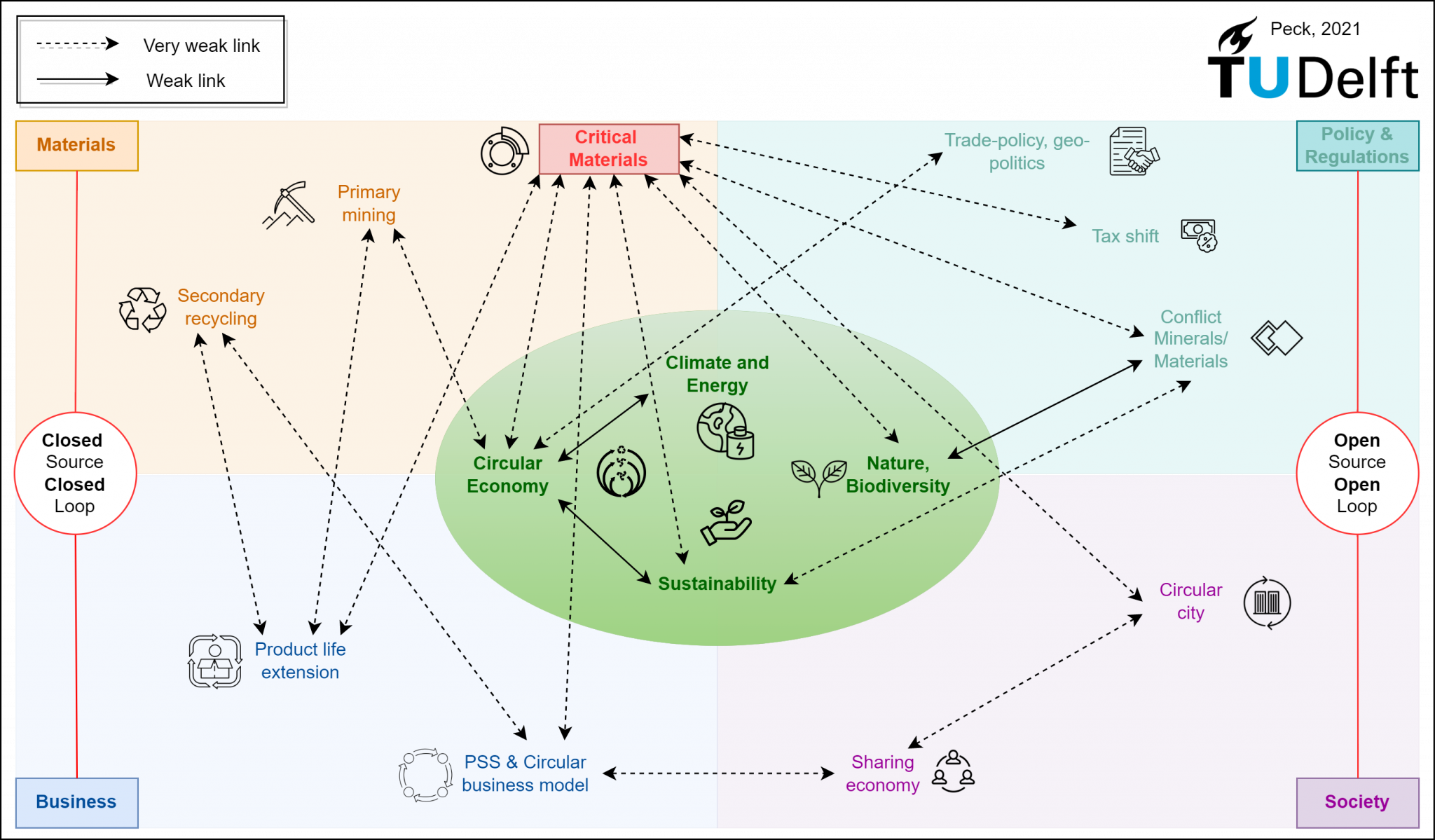

To Peck, there are parallels with the war in Ukraine as this conflict also forces us to rethink our global supply chains. “A major difference is that the current transition is led by the private sector with the encouragement of governments, while during World War II it was led by the state with the involvement of the private sector,” he says. He understands the reluctance of politicians to intervene, as they would face resistance from both the private sector and citizens. “The policy measures can perhaps be somewhat less draconian, but we do have to act fast and decisively, just like back then. So, we need some form of centralized control.”

Interest in critical materials on a policy level is higher than ever before, and Peck has been repeatedly interviewed by the Dutch media. “We are moving in the right direction, but not fast enough. The supply chains of critical materials are extremely dynamic and complicated. There are thousands of questions that need answering but, with all scholars specialised in this topic fitting into a single meeting room, we lack sufficient research capacity.”

Text by Karst Oosterhuis